Reforming Our Economic Management Team By Uddin Ifeanyi

From May 29th last year, the incumbent administration had 16 quarters within which to redress the fortunes of the economy. Any which way this task was contemplated then, it was always going to be a long shot.

Much of the recent impetus for slackening domestic growth has been the result of short-term downside risks: the abysmal management of the economy under the Jonathan government; the bottoming out of global demand (and hence of crude oil prices); the new restiveness in the oil-rich Niger Delta region, which is still taking such a severe toll on domestic crude production; etc. Still, all these reinforced the popular conceit that a well-run government would soon have us on the way to El Dorado.

That portion of the electorate that voted the Jonathan administration out on the back of this hope erred. Yes, we could pacify the Niger Delta over 16 quarters. And, we could stanch the fiscal leakages that hurt the economy over the same period.

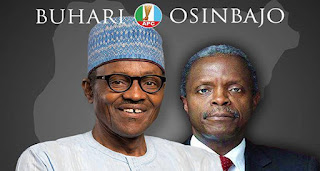

But, the challenge before the Buhari administration was never a near-term one. For starters, global demand was not part of its bailiwick; it could only wait and hope for a recovery over this current electoral cycle. Beyond that, though, is the doubt that the global economy could soon find the high gears that saw it chug along at a decent pace in the decades leading up to mid-2014.

Despite recent shenanigans around OPEC and Russia, the oil outlook has not improved. Global trade has tailed output growth in the last two years, reversing a trend that buoyed economies around the world before the last recession. Unfortunately, even if we could somehow flip this trend on its head, again, the prospects for US$100/barrel oil is dim. This is not just a matter of the supply glut in the market. It is about renewables accounting for a larger (and growing) share of electricity production in those places where fossil fuels were once dominant sources. It is equally about the car industry paying even closer attention to Elon Musk’s vision.

In other words, the global economy may be undergoing structural changes that will make it impossible for us to live as we were once wont to. These changes have always meant that simple tweaks to fiscal and monetary policy, even such as eliminating corruption, were never going to be enough to reset the local economy.

Even then, to go on about structural reforms, today, as if it were a novel solution to our problems, would be to ignore the extensive body of work available in the country on how to wean the economy off its addiction to crude oil export earnings. Going cold turkey was never one such solution; at least until the global economy forced it on us.

Now, then, the main task for any serious government in the country is to free the economy’s “animal spirits”. To reduce domestic “transaction costs”. To strengthen mechanisms for building trust, especially through better legal and law enforcement procedures. And to build domestic human capital — i.e. boost institutional capacity for delivering better education and healthcare.

None of the structural reform proposals for improving domestic economic competitiveness would bear fruit over the four-year electoral cycle. Indeed, over this period, even with fiscal and monetary policies in fine fettle, the populace is likelier to see more pain than gains from official reforms. I suppose this is where successive governments have parted with the courage required to put these convictions in practice.

In the case of the incumbent government, it has used up six quarters twiddling its thumb. Four of this six have seen the economy find a reverse gear. Now you need remember only that the last four quarters, the ones leading up to the end of the election cycle, will be taken up by polling concerns, to understand how precarious the outlook for this economy is.

So, back out those last four quarters, and all that’s left for this administration is about six quarters. On past form, it is unlikely to get fiscal and monetary policy right. Besides, 24 months is not time enough to commence serious reforms to the structure of the economy, and harvest the fruits of such reforms.

So, what to do?

If the administration were a business challenge, much easier to fully provision for it, seek to bring down domestic costs, rationalise operations, and raise new capital. However, this will be because, first, you have changed management.

Our main challenge then, if we were to extend this latter metaphor, is to reform and reinforce our electoral processes, so that it is cheaper and more efficient, come 2019, if we are minded to change the present management team.

Ifeanyi Uddin, journalist manqué and retired civil servant, can be reached @IfeanyiUddin.

Comments

Post a Comment