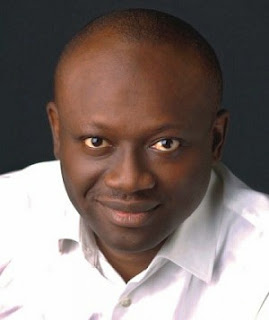

Nigeria: A Community of Contradictions By Simon Kolawole

This must be a joke. An armed robber, on realising that his gang’s victim was a born-again Christian, decided to pray for him. “Father,” he said, “everything we are about to take from your dear son, we ask that you replenish a hundredfold in the name of Jesus. We ask you, O Lord, to give him beauty for ashes and oil of joy for mourning.” It has to be a joke.

But nothing is impossible in our dearly beloved Nigeria. Our lives are so warped and senses so twisted that we are very comfortable with our contradictions. We don’t even see them as contradictions anymore. It is our way of life. It is who we are. We are incapable of stepping back a little to see any dissonance.

It is not uncommon for a gang of armed robbers to include a “pastor” and an “imam” who pray before and after operations. The robbers, of course, will later give tithes and zakat in appreciation of what “God” has done. I once read the story of a pastor who was selling “anointed pants” and “anointed bras” to young ladies travelling to Europe for prostitution.

Typically, a political or government meeting starts with Muslim and Christian prayers. Next, they move to the agenda of the day: contract inflation, looting, assassination and other evils. The meeting then closes with Muslim and Christian prayers. Amen. Ameen. And life goes on.

On Wednesday, in Abuja, Mr. Sam Afemikhe, a renowned chartered account, launched his book, Hope Rekindled: A Comprehensive Analysis of Nigeria’s Nationhood Challenges and How to Overcome Them (full disclosure: I was the book reviewer). In the 800-page book, he lays bare his diagnoses of the Nigerian condition as well as his prescriptions to treat our chronic underdevelopment. His diagnosis that strikes me the most, and which inspired today’s discussion, is in chapter eleven, with the title: “A nation of contradictions.” In it, he highlights how our actions and behaviour as Nigerians and as a nation “are full of contradictions” — insincerity and self-deceit.

Afemikhe illustrates the dissonance this way: we agree that government has no business in business but obstruct privatisation all the same; we agree that subsidy is breeding corruption and benefiting only a cartel but oppose any attempt to remove subsidy; we export jobs to foreign countries by voraciously consuming imported goods but complain that there is unemployment in the land or that the naira is losing value; we say we want accountability in government but demand “stomach infrastructure” when electing our leaders; we say we hate corruption but glorify looters with chieftaincy titles; we believe there is crime but politicise the punishment. Contradictions.

These contradictions are manifest everywhere all day long. I will pick on just two today and save the rest for another day. The first is the dissonance in our policies. We want to bring over 100 million unbanked Nigerians into the financial sector. We want financial inclusion. We want a cashless society. But as we gain on the one hand, we lose on the other because of the in-built contradictions. The second is our drive for foreign investment. We claim we need foreign investors to inject their capital and expertise into Nigeria and add value to the economy — but we harass, embarrass, intimidate, denigrate and scandalise them.

Let’s discuss the first sample. A major reason for the bank verification number (BVN) was to create a biometric system to bring unbanked Nigerians into the system. Since most of them are in rural areas and are barely literate, the BVN would allow them to operate accounts without having to sign cheques or passbooks. They would simply use their fingerprint, even at ATMs, to do banking business. As good as this idea is, the central bank jeopardised its own financial inclusion drive by constraining the growth of Mobile Money, most likely because of the influence of the banks who may be jittery that they would lose out.

Mobile Money uses mobile phones for financial transactions. If well implemented, it can accelerate financial inclusion, reduce transaction costs, minimise banking dangers and facilitate a cashless society. It allows users to deposit, withdraw and transfer money, as well as easily pay for goods and services with their mobile phones. Nigeria, with 130m active mobile users, should be leading the rest Africa in this department. But less than 20% of Nigerians are using Mobile Money — compared to Kenya, where 60% out of its 29m citizens are on board. Banks unsuccessfully tried to stop it, claiming it breaks financial regulations. Today, the Kenya success story has become a global model.

Why is it not pervasive yet in Nigeria? One factor, I understand, is that the CBN, as the financial regulator, would rather allow banks, instead of Mobile Money Operators (MMOs), to run the show. The licensed banks will then deal with the operators. This is a long route, and what has happened is that Mobile Money has become more of an extension of a bank’s services to its customers, rather than a system to bring in the unbanked through mobile telephony. Understandably, banks are worried that if they are not at the centre of things, MMOs may take over the financial system. CBN will naturally side with the banks even if it hurts the financial inclusion drive.

We are missing a lot. An awful lot. According to a recent report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a global research body, delivering digital financial services by Mobile Money could spur inclusive growth that will add $3.7tr to the GDP of emerging economies (Nigeria inclusive) in 10 years. It can create 95m jobs across all sectors within a decade. McKinsey identifies Nigeria as one of the countries with the largest potential — with an additional 10- 12% GDP growth on offer! While we officially say we want to “bank the unbanked” in Nigeria, we have practically slowed it by effectively limiting Mobile Money to bank customers only — to please the banks.

That is just one area in which policy pronouncement and practical application are worlds apart. This contradiction is also very evident in the way we treat foreign investors. As a nation, we say we want them. We want their billions of dollars to boost the economy, provide employment, and generally add value to our lives. Yet we make life so difficult for them for no sane reason. Look, for instance, at the way we treat MTN. No, I am not talking about the N1.4 trillion fine. That was, in fairness, a punishment for an infringement in the SIM registration exercise. They walked into our trap and gave us the opportunity to “deal” with them, but at least there was an infraction involved.

However, a lot of fuss was made recently about MTN’s repatriation of $13.92bn profits to South Africa from 2006-2016 — as if they stole our money. Foreign companies such as Shell and British Airways repatriate their incomes all the time — as allowed by the relevant laws. But MTN has become a punching bag for us such that virtually anything it does is scandalised and criminalised with relish. We expect Nigerian companies such as Dangote, Oando, Arik and Globacom to bring back their incomes from other countries. We expect them to be treated fairly and justly in any country they do business. But we antagonise foreign businesses in Nigeria. Contradictions.

In truth, a company like MTN that has invested over N3.2 trillion in our economy deserves a bit of our respect — as long as they operate within the laws of the land. Since they started operating in 2001, according to official figures, they’ve contributed over N 1.6tr to government coffers through taxes, levies and regulatory payments, providing jobs for over 500,000 Nigerians, directly and indirectly. MTN Foundation has spent over N18bn through CSR in almost every local government in Nigeria. They’ve disbursed over $3.5bn worth of businesses through adverts and sponsorships, and patronage of Nigerian hospitality industry and contractors.

Let’s ask ourselves an honest question: why are foreign investors no longer rushing to come to Nigeria? How can NCC auction lucrative frequencies and the big guys would not show interest? My hunch is that they are not impressed with our policy-cum-regulatory environment. Our mixed messages and arrogance are killing us. We behave as if there is no other country in the world where investors can make money. We need all the investments we can get to grow this economy but our behaviour contradicts our desire. Afemikhe, in his book, says our contradictions are a “fundamental hygiene factor” to address in our drive for development. I agree with him. Absolutely.

“It is not uncommon for a gang of armed robbers to include a ‘pastor’ and an ‘imam’ who pray before and after operations. The robbers, of course, will later give tithes, offering and zakat in appreciation of what “God” has done”

OBASANJO VS BUHARI

A Yoruba proverb says that “you help a man to get a job but you don’t help him to do it”. Many people who helped President Buhari win the 2015 election have come under heavy criticism over his performance in office. President Olusegun Obasanjo, who endlessly savaged President Goodluck Jonathan to help pave the way for Buhari, appears to be losing faith: he admonished Buhari to stop whining and get on with the job. Instead of describing this as the usual “corruption is fighting back”, Buhari would do well to reflect on his ways. Even though he evidently inherited a failing economy, blaming Jonathan day and night can never be a recovery plan. Action.

FAMINE FALLACY

Nigerian grains are being “heartlessly” exported, a presidency official said, and there would be famine very soon. Really? I would think if Nigerian grains are so loved abroad, we should rather develop a strategic programme to increase production. There is apparently a foreign market for our grains, no? Meanwhile, government has been asked to ban the export of grains to save us from an impending famine. Really? I thought government should instead buy the grains from the farmers and store in our strategic reserves. Are these economic principles so difficult to comprehend? Why do we always think the best way to treat headache is to cut off the head? Baffling.

DEVIL’S DEAL

Many Nigerians were shocked when Mr. Jimoh Ibrahim said, at the Ondo state governorship debate on Monday, that he would abolish personal income tax. In the field of Fiscal Sociology, there is actually a theory called “Devil’s Deal”. Politicians in underdeveloped, resource-dependent countries tend to pay less attention to tax so that the citizens will not become too interested in holding the government accountable. There is a way tax hurts and instigates campaign for accountability. The devil’s deal is to look the other way when it comes to taxing your citizens — so that your citizens too can look the other way when you are mismanaging their resources. Reciprocation.

IN MEMORIAM

Today makes it exactly 40 years that my father, Mr. Boniface Kolawole Gabriel, died after a motorbike accident in front of Unity Hotel, Ilorin, Kwara state. He was still breathing when he got to the hospital, but help was too late as the hit-and-run driver had left him to his bleeding fate. Only my elder sister (who died last year) and myself had faint recollections of our dad. My three younger siblings did not even know him. The youngest was just six weeks old at the time! Having lost her husband at 31, my mum must be Nigeria’s longest serving widow. She refused to remarry, retorting: “What else do I want? I have boys and girls.” She talks fondly about our dad till this day. Memories.

Comments

Post a Comment