The problem with monetary policy by Mike 'Uzor

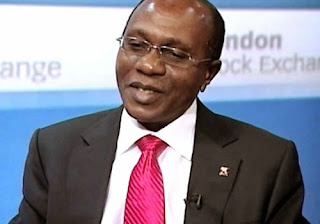

The major outcome of the last meeting of the monetary policy committee of the Central Bank was a warning. The bank’s governor, Mr. Godwin Emefiele, warned that the economy was headed for a protracted recession unless what he described as “bold monetary and fiscal policies” are taken as a matter of urgency to sustain the economic recovery momentum. This means in clear words that even a fragile economic recovery expected this year now stands a big risk of being scuttled.

Speaking of bold monetary and fiscal policies clearly lays the responsibility for the needed actions on both the government and the Central Bank. The governor was therefore sounding the note of warning to the bank he governs as well as to the government. Government’s snail speed response in terms of appropriate fiscal action has been obvious since last year when budget approvals and implementation have suffered unwarranted delays. But where is the boldness in monetary policy that Emefiele is calling for?

It is apparent that the Central Bank failed to set an example of the boldness it was calling for by perhaps dropping the monetary policy rate from 14% to a single digit – to give users of bank credit a little breathing space. The committee also left the cash reserve ratio unchanged at 22.5%, leaving us wandering what else the bold monetary policy could be.

This means the committee decided to continue to freeze more than one-fifth of bank deposits at zero interest rate thereby maintaining the seal on bank lending capacity. Yet, it went ahead to call on banks to reduce interest rates without setting the pace – a good example of a call that will fall on deaf ears.

The monetary policy committee rightly identified weak financial intermediation as the first of the three main downside risks to Nigeria’s economic outlook. It is quite clear that this problem lies within the domain of monetary policy, requiring the application of the strength and the boldness the Central Bank itself has recommended.

It is clear that the Central Bank is seeing the risk ahead and knows what poses the risk [weak financial intermediation] and is yet unwilling to address it by strengthening financial intermediation. Where then are the boldness and the urgency in monetary policy it is calling for? As in the case of interest rates, the bank is again calling on banks to increase credit delivery to the economy while it decided to keep a good part of their liquidity frozen – another typical case of a call that will land on deaf ears.

Banks themselves have continually come under severe survival pressure. The Central Bank’s governor is rightly concerned that the prolonged weak macroeconomic environment has continued to impact negatively on the banking sector’s stability. He however failed to state any steps the regulatory institution is taking to address the sector-wide problem.

Rapidly growing credit losses is a real threat to the banking sector generally in respect of which the Central Bank needs to engage policy actions that reinforce the liquidity of banks and ease the pain of borrowers. The call by the monetary policy committee for intensive surveillance of individual banks isn’t the policy instrument needed to address the effect of the weak macroeconomic environment on the banking industry. A case by case management approach that the CBN said it is applying isn’t going to be an appropriate response to a general industry problem that hinges on a faltering economy.

The Central Bank seems to be placing undue emphasis on inflation, which has become an excuse for failing to adopt a pragmatic approach to monetary policy engagement. Emefiele is calling for fiscal stimulus to step up economic activity and yet he is quite nervous about inflation. He recommends a relentless fiscal stimulus in order to drive economic growth and yet he is kicking against the government’s N2.51 trillion fiscal deficit incurred in the first half of this year.

Fiscal injections strong enough to spur economic recovery can be expected to spur inflation normally. It is the duty of the Central Bank to manage the effect of fiscal actions on financial markets to attain stability. There is no way the ‘strong and bold’ fiscal action the bank’s governor is calling for isn’t going to be inflationary.

Inflation itself is presently the lesser evil and a sort of fallout that should be expected in the process of pursuing the overriding objective of propping up recovery and stimulating growth. The present monetary policy stance isn’t going to let economic growth take root if the Central Bank’s focus on inflation is rigidly maintained. What will happen is that it soaks off fiscal injections and keeps the spending from stimulating output.

Monetary policy has assumed a central role in macroeconomic policy framework in every modern economy. It activates rapid responses that lead to the appropriate adjustments desired in the policy objective. That makes it a short cut to achieving economic and financial markets stability and an acclaimed tool for preventing wide swings of economies and markets.

The effective treatment of the last global financial crisis happened within the realm of monetary policy. Monetary policy easing has been the main tool of the US’ monetary authorities for stimulating the economy since the global financial crisis. The UK prevented economic recession by pumping new money through the banking system to empower producers and consumers.

Close to 18 months since the Nigerian economy plunged into recession in the first quarter of 2016, the authorities are still talking and warning about what needs to be done. As was the case last year, the Central Bank is dumping the blame for recession on the fiscal authorities and is posting a body language that it has done the monetary policy bit of the job. This is even as its monetary policy committee voted out the minority view of using monetary policy easing to prop up economic activity.

Keeping monetary policy stringent in a declining economy is a pro cyclical approach, which reinforces the decline. The last global financial crisis could have continued to linger if that was the approach. Keeping the credit markets frozen and calling on banks to open credit windows is a matter of just to say something.

Leaving monetary policy rate hanging at 14% and calling on banks to reduce interest rates is nothing better than a show of good intent. Until the bank is able to adopt a broad based framework that makes monetary policy stimulatory to domestic production without hurting financial markets, the journey out of economic recession cannot truly begin.

‘Uzor is a financial analyst

Comments

Post a Comment