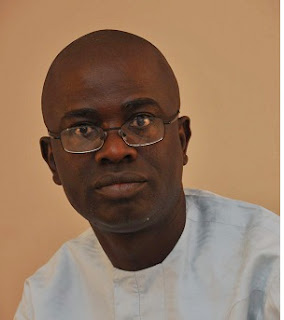

My 2020 Take Away By Olusegun Adeniyi

Last week, I recounted my family’s twin ordeal of an armed robbery attack and COVID-19 infection in my column, ‘Gunman, COVID-19 and My Family’. Unfortunately, the publication came on the day we had to move my son to the National Hospital Isolation Centre where he spent Christmas and subsequent days before his eventual discharge. That was why I couldn’t pick (or return) many of the calls or reply to messages I received that day. I am grateful for them all. Paired in a room with a distressed man placed on oxygen, my son experienced considerable trauma and made life difficult for my wife due to his constant updates on phone. But there was nothing we could do to help him. His recall makes him eligible to co-author, with ‘Twitter diarist’, Mr Gbenro Adegbola, an interesting book that would put the fear of God in the hearts of all Covidiots!

One of the WhatsApp messages in circulation as a seasonal greeting is the prophetic reflection by Okonkwo, in Chinua Achebe’s novel, ‘Things Fall Apart’, on “the worst year in living memory”. During that tragic year, which Okonkwo reportedly remembered with a cold shiver throughout the rest of his life, “the harvest was sad, like a funeral and many farmers wept as they dug up the miserable and rotting yams. It always surprised him when he thought about it later that he did not sink under the load of despair. He knew he was a fierce fighter, but that year had been enough to break the heart of a lion.” Okonkwo’s parting shot: “Since I survived that year,” he said, “I shall survive anything.”

What Achebe was telling us through one of the most complex fictional characters of the last century is that nothing compels introspection better than adversity. And I expect we all have our varied experiences on a year that we can never forget. It is the same for our country.

On several fronts, 2020 has been a horrible year for Nigeria. Despite being repeatedly declared ‘technically defeated’, Boko Haram and terror affiliates have killed (mostly in ambush) hundreds of soldiers this year. They have also murdered thousands of innocent citizens, especially in Borno State. With Katsina (home state of President Muhammadu Buhari) as the epicenter of growing violence in the North-west, bandits, kidnappers and other sundry criminal cartels have overwhelmed the capacity of the state to widen ungoverned spaces in Nigeria. And since when it rains for our country, it actually pours, the economy is again in recession—its second contraction in five years—amid a global pandemic that has disrupted lives and livelihoods for the majority of our citizens who now live below the poverty line. It was also a year of resistance by young Nigerians who used the EndSARS protest to send a clear message to the licensed thugs in police uniform: Thus far and no more!

As we reflect on the challenges of the outgoing year, it is important to also look at the lessons we have learnt as individuals and as a nation. I want to draw from my own personal experience. From the good to the bad and the ugly as well as the pleasant, 2020 has enriched me in numerous ways. Even in adversity, I choose to look at the bright side of life. I can write a whole book on my experiences this year but what strikes me the most is a simple conversation I had on 28th October with my mentor, Professor Jacob Olupona, NNOM, FNAL, of Harvard University at his Arlington (MA) residence. Perhaps this is also because it took a tiny virus to teach us the significance of small things. As one writer most poignantly put it, “the busy culture bubble popped and we were rewarded with the opportunity to create space for ourselves and find a stillness rarely afforded in modern life.”

Whenever in the United States in the past ten years, I have been a guest at the home of the Oluponas. This particular trip was no different, despite the risk to their family of taking in someone whose Coronavirus-status they had no way to vouch for. On my first day, the discussion with Olupona began with the usual Nigerian lamentations before we moved to his memoir (still in the works). He shared with me insights from his days as an undergraduate at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN) and at a point paused to say, almost solemnly, “The only regret Dupe (his wife) and I have is that despite all our efforts, we haven’t been able to reestablish contact with Mrs Awa. It’s either she is late now or has moved back to her ancestral country, Sierra Leone. Obinrin yen ma toju wa o (that woman really took good care of us)”.

When I interjected by saying “Mummy Awa?”, Olupona looked at me curiously before he replied, “You don’t know the woman I am talking about. She was wife to the late Prof Eme Awa who was briefly the chairman of INEC (Independent National Electoral Commission) under (General Ibrahim) Babangida. Her husband was an institution at Nsukka then. A very good man. So is his wife.” Olupona continued to eulogise the Awas and how they made a difference in the lives of several students at Nsukka in the seventies.

I said again, “Mummy Awa?”

Until she moved to Lagos a few years ago, ‘Mummy Awa’ as we call her was a worker at The Everlasting Arms Parish (TEAP) of the Redeemed Christian Church of God. The founding parish Pastor, Chinedu Ezekwesili, who made all members act as one big family, had drawn me close to the simple woman we all loved. Her daughter, Uzo, and my wife struck a friendship and with that her grandson (Kester) also became a friend to my son. Since the descriptions fit, I knew we were talking about the same person. “Which Mummy Awa do you know?” Olupona asked.

I took my mobile phone and dialed a number. Given the time difference with Nigeria, I wasn’t surprised that Mrs Awa didn’t pick my call so I sent her a WhatsApp message. About two hours later, she called me back. I just handed the phone to an excited Olupona. When that first conversation ended, Olupona said something I will never forget: “We have been searching for any contact to this woman for the past six years. You don’t know the import of what you have just done. Maybe your trip to America this time was divinely arranged so that we could connect with Mrs Awa. My wife and I can never forget the role the Awa family played in our lives.”

Throughout the two weeks I spent in the United States, Mrs Awa was the subject of conversation in the home of the Oluponas. They had just too many interesting anecdotes to recall. Mrs Dupe Olupona (also a student at Nsukka at the time) said it was at the home of the Awas that she celebrated her 21st birthday.

Since Prof Olupona graduated from Nsukka in 1975, it means that all the stories he and his wife told about the Awas were things that happened almost 50 years ago. Without any expectations, and despite no prior relationship of any kind (except that Mrs Awa is a Sierra Leonean Yoruba), the Awas took the Oluponas under their wings as they did several others at the time. And today the Oluponas remember those acts of kindness and selflessness. That is impact.

As an aside, Olupona recounted for me the interesting drama leading to his employment by the then University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) not long after his National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) primary assignment. He was considered as an ‘outsider’ by Ife professors on account of being an ‘Nsukka Boy’ (which he gladly owned). Despite his impressive resume and outstanding performance at the interview panel, Olupona was almost denied employment in an institution that gladly welcomed his friend, Andrew Igenoza—who later became a Bishop of the Anglican Church—because he (Igenoza) graduated from Ife. While Olupona (who taught at the University of California for 16 years before arriving at Harvard in 2006) argues that our universities must overcome the culture of inbreeding that runs counter to innovation and creativity, I see something else in his fascinating story. In the Nigeria of today, Olupona would have been gladly accepted at the University of Ife as an “Omowale” (our child has come back home). Meanwhile, at the same UNN that Olupona unceasingly eulogises, it is not even enough to be Igbo to be accepted as Vice Chancellor. You must hail from Nsukka town!

Incidentally, when in 2015 Ife awarded Olupona the honourary doctor of letters, it was hailed on the campus as a homecoming. When Olupona visited the University of Carlton, Canada, at the invitation of my late friend, Pius Adesanmi to present a lecture to the Yoruba Community in the country, the then Nigerian High Commissioner, late Chief Ojo Madueke, paid tribute to the academic achievements of the Yoruba, adding that the proof was that we were the first to produce Harvard professors. In response, Olupona reminded Madukewe that Prof Onwuka Dike, the pioneer Nigerian Vice Chancellor of the University of Ibadan, was at Harvard long before Biodun Jeyifo and himself. In 1973, Dike became the first Mellon Professor of African History and later, chairman of the Committee on African Studies at Harvard—a position Olupona occupied between 2006 and 2009.

All said, there is a lesson in the Awa story for both the season and the future to which we aspire as individuals and as a nation. Regardless of our ethnicity or religion or whether we are rich or poor, powerful or weak, a tiny virus that does not discriminate in picking victims has taught us that we all belong to the community of humanity. It has also helped to connect us in a manner that speaks to how our strength lies in remembering that life is a gift we must cherish. The Awas focused on what was important. They were modest lecturers whose primary duty was to model students. And they succeeded brilliantly. They made a difference in the lives of people who five decades later, still remember.

The bane of Nigeria, as we all glibly say, is failure of leadership. But it is beyond Aso Rock. It is at every sphere and in all sectors, including in the strike-obsessed academia. I have followed the heartbreaking story of the JSS1 student who was brutally molested at the Deeper Life High School in Akwa Ibom State. If such abuse and criminality can happen in a faith-based school where parents pay exorbitant fees, one can only imagine what happens in our public schools where anything goes. Based on the response of authorities concerned, it is easy to see that there is more interest in managing the optics than the welfare of the traumatised boy. As I have argued in the past, the tragedy of Nigeria is not only in the failure of government but rather in the collapse of values and ethical mores in the society. For things to change, we must all resolve to be better people. Kind. Considerate. Selfless. That duty of care for others demonstrated by the Awas in the seventies is the spirit we need to rebuild our country.

In his opening remark at the Global Solutions Summit 2020 in June this year, founder and president, Dennis J. Snower, a Berlin-based Professor of Macroeconomics and Sustainability, argued that 2020 has brought us face to face with the most basic questions of life. COVID-19, according to Snower, has revealed “how terrible it really is to waste our lives, embroiled in endless battles for wealth and status and power. How terrible it really is not to recognize the value in the people around us – not just our family and friends, not just colleagues and fellow citizens, but also complete strangers.”

As individuals and as a nation, it will be a shame if we enter 2021 with the mindset of the past. The pandemic, in the words of Snower, “has impelled many of us to use our greatest strengths to serve our greatest purposes, suddenly giving our lives new, inspiring meaning.”

I wish my readers a healthy and most prosperous 2021!

Comments

Post a Comment